Weather Forecasting Versus Climate Forecasting - Dimension Analysis

This post is not about what you think it is about.

“Predictions are hard, especially about the future.” — Marty McFly (in spirit)

Reading this post from Tim Harford got me thinking about predictions and how to analyze them along various spectra.

One interesting comparison that I’d like to consider is how predictions can be likely or unlikely. This is another way of saying their accuracy will be either easy or hard.

Another would be how they can be useful or useless, which perhaps surprisingly does not correspond to them being applied or incorporated into behavior or choices. Harford speaks to this directly in the post:

My non-answer was weaselly, yes. But the exchange points to a problem: producers of forecasts frequently give people warnings they ignore, and unless consumers of forecasts are honest with themselves about what they plan to use them for, their demand for a glimpse of the future seems fatuous. Or, to quote George Eliot, “Among all forms of mistake, prophecy is the most gratuitous.”

This brings me to the comparison: weather forecasting versus climate forecasting. These are general terms not at all specific to their literal meaning.

Sometimes predictions are like near-term weather forecasts: likely and useful.

Sometimes predictions are like long-term climate models: unlikely and useless.

This is not an attack on belief or disbelief in climate change. Regardless of your position on climate change (informed or not; zealous or agnostic), it is unarguably a very difficult task—making unlikely any specific predictions are accurate—and it really doesn’t inform us much about anything specific we individually should do.

Climate is a stand in for long/far events and scenarios. Climate is inherently more difficult and less useful. Hence, many people commonly disregard it while others engage in mood-affiliating behavior that has little to no connection to changing outcomes.

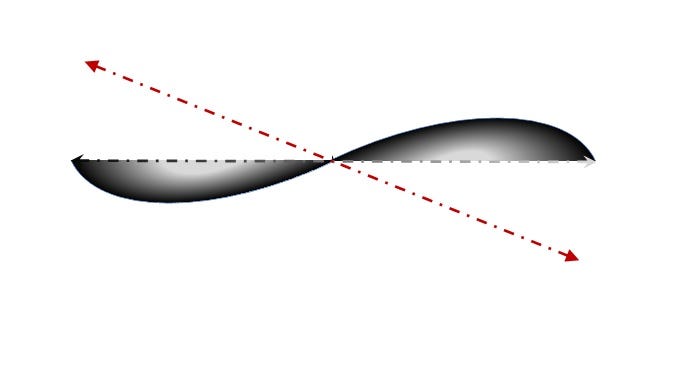

Since we have actually two dimensions to draw comparisons along, this really presents as a 2 x 2 matrix.

I would like to frame this discussion within the context of current economic conditions about whether we will have a recession. That has us in the northeast quadrant: knowledge we probably could usefully put to work if we only had a chance of knowing it.

In my work of investment portfolio management I get a lot of questions about where the economy is heading. In recent years that has increasingly included questions about inflation. Always it has included questions about recession. No one likes the honest answer: I don’t know, and no one else does either.

The best anyone can do is discuss the recent trend, which is usually highly useless since your individual recognition of it is always quite a ways behind the market. Additionally a decent forecaster would be able to describe the likelihood of a recession in relative terms.

The best forecaster could only boast something along the lines of “my calibration between the expectation of the likelihood of a recession (low or high) corresponds to an actual recession (there is one or there isn’t one) about 60% of the time.” Which is another way of saying: “60% of the time it works every time.”

Forecasters’ track record on inflation would only be more accurate for those with low base rates since inflation has been largely absent our economic battlefield for the last 40 years—2021-2023 are the only outlier.

When it comes to unlikely forecasting, I would suggest combating it by defensive positioning that doesn’t require accuracy. In other words take precautions, keep options (exposures) alive, and [edited: avoid anything requiring] require accuracy in any case.

Imagine our ancestors who did not know if storms were coming (tomorrow)1, but they knew that storms were coming (eventually). They needed to take precautions like not travelling too far from shelter without temporary plans in case a storm developed. They also needed to build structures and position assets such that when a storm came they would be relatively prepared. In a more climate-oriented way they knew winter was coming, summer would be hot, and rain might fall a lot including too much or not at all.

Specific to portfolio management, the general answer is a long-term plan that mixes risk/return so as to very likely achieve long-term goals while making short-term ruination exceptionally unlikely. A portfolio where everything has to go right is doomed to failure. A portfolio where everything going right still doesn’t get to the destination is also doomed to failure.

As Harford concludes:

For a forecast to be useful, it is neither necessary nor sufficient that it be accurate. That might seem a bizarre claim, but we only know whether a forecast was accurate when it is too late. In advance, what we can hope for from our prophets is that they open our eyes to different plausible futures, motivate us to anticipate threats and opportunities and remind us that, in the end, the future cannot be known. It can only be imagined.

I don’t want my portfolio to require accurate prediction (that’s a fool’s errand). I want it to be prepared for the potential of a recession as well as the avoidance of one. This is itself a form of diversification.

There are lots of places like this, but I am always a bit amazed how in Oklahoma it can be absolutely beautiful one day and disturbingly dangerous the next. “If you don’t like the weather, just wait” is a phrase I’ve heard about basically everywhere except San Diego. While no place can uniquely claim it, it speaks to a world where precautionary preparation is needed.