One of the things you learn early on in studying logic is to identify common fallacies (errors in reasoning) that corrupt arguments making them bad and therefore dismissible. Once you learn them, it is impossible not to see the most common ones in their most common versions out in the wild.

This can be frustrating as it is often hard to get opponents to understand why the argument they think is so strong is completely defective. And to be honest this can generally expose a weak or lazy thinker that one should not waste one’s time arguing with.

Not that identifying logical fallacies is always easy by any means. There are false positives.

There is a subtle distinction between the following two arguments.

A1: John claims all of his pets are cats. But John cheated on his wife. So his pets are not all cats.

A2: John claims all of his pets are cats. But John cheated on his wife. So we can’t be sure about his claims about his pets.

A1 is fallacious—a completely bad argument. A2 is likely not fallacious. We should consider John’s character in evaluating his reliability.

That type of consideration as well as that specific type of fallacy—the ad hominem or argument against the man (ad hominem circumstantial to be precise)—is at play when it comes to the charge of hypocrisy as a tool of argument. The moral consideration of hypocrisy is another matter altogether.

Bryan Caplan has a very insightful look into the use of the hypocrisy accusation as a tool of argument. It dovetails with my thoughts on when the accusation has merit and when it is an illogical distraction, but his is better formulated than what I’ve come up with before.

I have always thought about how people’s taste and opinions are theirs to hold without question right up until the point that their stated reasons for holding them contradict the opinions themselves. E.g.,

Various football fandom like “I root for championship football” does not support rooting for a team that rarely competes for championships

Morality as a reason to vote for one’s preferred candidate like “moral character matters to me” does not support voting for . . . [checks notes] . . . basically any recent presidential candidate.

Positive attribute claims (social desirability bias) that don’t match behavior like thriftiness when spendthrift profligacy is evident.

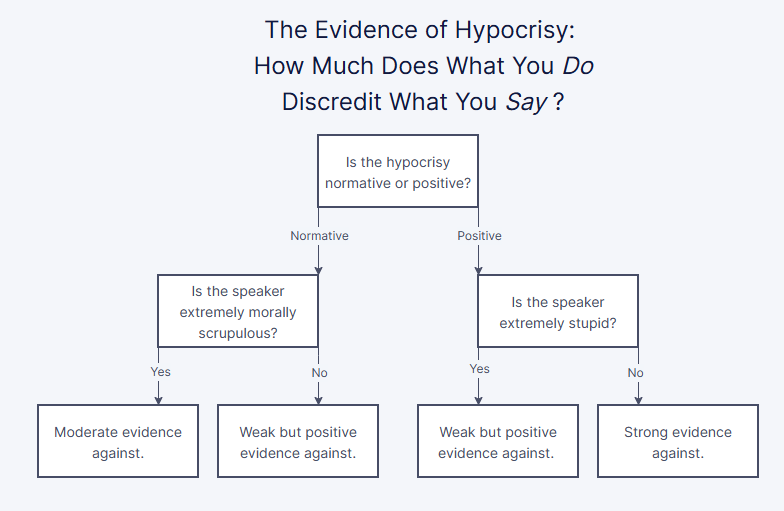

Very helpfully he offers this flowchart1:

He concludes,

While this is only a first pass, I’ll still pronounce it a major advance. Contrary to demagogic insinuations, hypocrisy is rarely decisive evidence that anyone’s views are false. But contrary to hypocrisy’s urbane apologists, hypocrisy is almost always at least slightly discrediting. In special circumstances, even normative hypocrisy is pretty discrediting. And except in special circumstances, positive hypocrisy is extremely discrediting. If your actions show that even you don’t believe you, why should anyone else?

Relatedly, Maxwell Tabarrok offers a strong critique of conservation environmentalism arguing that it has consistently (hypocritically) worked against two of its stated goals: promoting naturalism and fighting pollution. In it he identifies what might be the underlying reason behind its self sabotage: a loathing of change.

These hypocrisies are specific to the conservationist motivation for environmentalism. This motivation is a green-washed aversion to change of all kinds. Conservationists are willing to invade and intervene in the natural world to preserve their preferred image of nature. They are willing to induce millions of tons of carbon emissions and millions of lives worth of air pollution to prevent the construction of a solar farm or power plant that they don’t like.

Claiming a goal and then actively working adverse to that goal is a hypocrisy that disturbs me. Yet my biggest concern about the reaction it stirs up, that it is just me irrationally claiming hypocrisy!, seems unfounded at least in the ways I try to use it.

Argument based on a charge of hypocrisy can be quite strong reasoning. It can also be the tool of the fool.